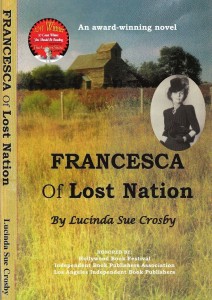

First 3 Chapters: Francesca of Lost Nation

Foreword

My name is Sarah, which is a Hebrew name and translates to the word “princess.” Of course, my German-American family was actually Presbyterian.

As a young girl, and throughout much of my life, I had the honor and privilege of knowing and loving a most remarkable, graceful, vigorous, resilient, eccentric, stubborn and fascinating woman.

She was never petty. She was never dull.

This is our story.

Chapter 1 Morning Music

I write of a morning in Eden … or, more precisely, in Lost Nation, Iowa in June of l947.

A pale melon of sun peeked over a strand of rolling hills and, safe and sleepy in my bed, I could hear our red-shouldered hawk calling to its mate.

It was another sunrise, a heavenly first-of-summer dawn of the most memorable year of my childhood. Adventure awaited me. The ancient oak down the hill beyond the weathered split-rail fence begged a climbing. I could also hear the cool depths of the fishing pond whisper my name. But first, the aroma of sweet cornbread, just done, tickled my nose. All other plans would have to wait.

In the glory of my nine soft years, I loved the unfolding of this new day. I could already hear my father’s off-key hum as he shaved himself. My mother, I knew, had been awake one whole hour, making magic in the kitchen on her vast black stove. She cooed to it and wooed it like a lover and in return, it always delivered up to her fine hands a golden bounty: Thanksgiving turkey stuffed with cornbread dressing, sourdough griddle cakes and Sunday chicken dinner with au gratin potatoes. Better than a pirate’s treasure. Better than a king’s ransom.

My room was white-washed pine. The wood floor was covered with a rug woven by my Grandmother Francesca’s graceful hands. I remember the many months she worried over it. On my eighth birthday, when she presented me with her prize, I received it with a proper reverence. No queen ever got more on coronation day, so delicate were the stitches, so fine and pearly the threads.

I never called her anything but Francesca, for that was her name to me. Not Grandmother, not Nanny, or Gran, not even Frances … but Francesca. Especially Francesca when the giggling got to us. My grandmother was regal. She was leggy and gracious and full of life.

Since it seemed that Francesca must be awake on this fine day, I slipped from underneath an ancient coverlet that was light as air. It had belonged to Great-Great Grandmother Mendenhall, and I loved its worn softness. I tiptoed down the hallway to Francesca’s boudoir.

Of course, it was really just a bedroom, but Francesca’s spirit made it seem much grander. Armfuls of summer blossoms cascaded out of old wine decanters. I can still remember the faintly odd scents which filled the air: Witch hazel; rose sachet and spice oranges, all capped by the aroma of lilac powder.

In the same way I did each morning, I tapped lightly on her door, once, twice, three times. I heard her stretch lazily, rustling under her often-washed sheets. A low voice called out softly. “Who is it?”

And I answered, in as stately a voice as possible, “Madam, your chariot awaits!” With the tingling anticipation that I felt every morning at Francesca’s private chambers, I listened for the invitation. Heart beating, toes curled under, I finally heard the words that never failed to delight me: “Come in, Sarah. I have missed you all night long.”

As I opened the cracked walnut door, which smelled of lemon oil, I was blinded by the sunlight that streamed in through open-weave curtains. Francesca never pulled drapes against the outside world.

She didn’t “put any faith” in drapes. Sunlight and moonlight were made welcome to fill her boudoir however they pleased.

“It’s going to be hot today; I can already tell,” said Francesca with a sigh.

My grandmother thrilled to the spring rain, to the winter sleet and snowdrifts, but she disdained the humid, baking days of the Iowa summer.

“Well, we’d better begin what we’re about while I still have a breath left in me,” she said and then sighed again.

That’s when I kissed her, right on the top of her gray-brown head.

“I’ll bring café au lait,” I promised, already skipping to the narrow rear stairway to the kitchen.

My mother was standing in front of the black stove, whispering encouragement.

“I need you to be just a little hotter now. Yeeesss … my, my, that’s perfect.”

Without interrupting her flow of praise, Mother pointed to a rosewood tray in the center of a long trestle table. Covered with a fine lace cloth and set with see-through porcelain cups, the tray looked like an outsider. It was a touch too exotic, a touch too elegant for a farmhouse … much like Francesca.

The dining set was a part of the honeymoon treasure Francesca and my grandfather Cox had brought back from New York City.

Cox and Francesca were married for many years. High school sweethearts they had been, different from one another and from everyone else in Lost Nation. They argued and danced and high-kicked their way through life like a pair of matched grays. Francesca was always the wood nymph, cool and moon-covered; Cox was the imp gambler, reckless and roguish. They lived honestly together, yet there was a separation, too, if that’s possible … each respecting above all else the right of the other to grow. Their marriage wasn’t a match made in heaven by any stretch, but it was lively and full of surprise.

Cox died in 1943, and I’m not sure that Francesca wasn’t still mad at him for leaving. Her father had warned her forty years earlier that would happen, and it galled Francesca that Cox had eventually proved the old man right, even if it took untimely death to do it. Francesca was no fan of “untimely death.”

Mother was at the stove, cooking, and I heard her humming the words to one of my father’s favorite tunes: “Cool Water.”

Her voice, unlike Daddyboys’ raspy, wrong-noted instrument, was low and firm.

She poured coffee from the spotted-metal pot into the two cups on the tray and added warm milk still smelling of hay and cow. From the tin breadbox, I snuck two crumbly squares of cornbread and topped the feast off with a crock of butter. I kissed my mother then and hugged her.

She hugged me back in the sweet but dismissive way mothers do when their minds are occupied. That’s when it struck me that something wasn’t quite right in the house this morning. But for the life of me, I couldn’t put my finger on it.

I took up the tray — swept it up, really — and with a great flourish and a curtsy, I took the meal Mother had prepared for Francesca and carried it carefully up the back stairs. Then, with one foot in front of the other, I made my way down the center of the hallway. It was important, staying to the center. I never wanted to offend one side by showing too much attention to the other. For the same reason, I sat on all the chairs in the parlor, even the scratchy horsehair sofa, in rotation and never wore a shirt more than one day at a time.

I set the tray on the floor by Francesca’s door and knocked again.

“Madam, your morning sustenance.”

“Do come in,” said Francesca as she opened the door for me, taking the heavy tray and setting it on the delicate walnut dressing table by the window.

There were thirteen antique silver frames on that table, each one containing a photograph of members of our family. The only one not represented in the collection was Francesca’s own sister, Maude. My grandmother had a prejudice where Maude was concerned, and it didn’t do to ask about it. All you’d get for your trouble was a frosty stare. No, it didn’t do at all.

As we nibbled and sipped, I watched Francesca finish her morning toilette. She was wonderfully long-limbed. As a girl, her legs had been judged the best in the county by the group of boys she’d grown up with. But she would have preferred to have had the beautiful face of her sister Maude and often said so. (I would have traded mine for Maude’s too, for that matter.)

But even in her workaday outfit of any old shirt and patched cotton trousers cut off at the knees for coolness, you couldn’t get around Francesca’s lithe shape and queenly bearing. I’d seen pictures in LIFE magazine of Princess Elizabeth, the future monarch of England. But I thought Francesca was much better suited to the job, both in appearance and personality.

I sat on the bed and watched as Francesca brushed her bobbed hair in her usual off-hand manner, despairing of the wisps that formed around her forehead in the humidity.

Francesca had taken to wearing her wedding ring around her neck on a gold chain. She fingered it contemplatively as it caught the light from the window. She sighed and turned abruptly to face me.

“Is there something odd going on in the house this morning?” she asked.

“Yes,” I whispered.

So she’d noticed it, too. I shouldn’t have been surprised, because Francesca was as canny as Sherlock Holmes.

“Listen,” she said.

We could hear my father’s scratchy baritone struggling:

“Quand il me prend dans ses bras

Il me parle tout bas… hmm hmm la da da di…

La vie en rose …”

Now that was certainly odd, since Daddyboys — that was my father’s nickname and how I referred to him — was a true-blue Country Western music fan. His all-time favorite was Roy Rogers and the Sons of the Pioneers.

“I don’t get it,” I said.

“It must be a mystery,” said my grandmother, teasing me, because she knew I didn’t like to be in suspense. I always wanted to find out right away what was going on. I thought my mother had been acting occupied while cooking breakfast. Now my father was singing strange songs. It was all too puzzling.

“Let’s talk to Daddyboys right this minute,” I said.

Patience was a quality I possessed only in dribs and drabs. Francesca, on the other hand, was a great one for the proper thing in its proper time, and she had the patience of a stone carving.

Christmas presents on Christmas morning, never Christmas Eve. Lunch after noon, never before, no matter how much your stomach growled. Resolutions harvested when the moment was ripe, never until. So it was with mysteries.

But suspense in our own household was more than I could endure and I wanted to know everything now. Whining, however, would get me nowhere. My father was not to be questioned, and that was final.

“Stop sniveling, Sarah,” Francesca warned. “He’ll tell us when he’s good and ready. I’m perfectly content with that.”

“What if he doesn’t?” I continued to persist.

“Then you can ask him,” was all Francesca offered as a response.

Impasses like these were a frequent pitfall in my conversations with my grandmother. She had many of the qualities of a fairy-tale princess, not the least of which was imperiousness.

I got my pig-headedness from her, make no mistake. We might easily have gone on this way for an hour without either one of us giving in. We’d done it often enough in the past.

But, like the Indians say, “Those who fight and run away, live to fight another day.”

So I threw my hands in the air and turned the conversation around a corner.

“What chore shall we do first?” I asked.

Francesca lifted her pug nose toward heaven.

“Why, whatever you like, Sarah,” she purred, magnanimous on the field of battle, victorious.

Chapter 2 Summertime Chores

He was the premier mechanic in a twenty-mile radius. My father enjoyed a thriving business and he also often burned the midnight oil. Sometimes, Daddyboys would stay at the shop for fourteen hours at a stretch, keeping the town’s outlandish cross-section of cars, trucks and tractors in good running order. In the summer, when the touring season was at its height, he had more work than he could handle.

My mother was a cook of considerable repute. I swear her pie crusts melted on contact with your tongue. In fact, Daddyboys insisted that she’d made a pact with the devil when it came to flour—“No lump would ever dare show its ugly face in her gravy,” he’d tease. Her biscuits were light as air; her canned fruits and vegetables were spiced with unusual seasonings of her own devising. She spent her days with her beloved stove, creating delicacies that sold briskly at Porter’s Emporium, Lost Nation’s sole general store.

It was up to Francesca and me to keep the farm running while my parents worked, so most of the daily chores on our property fell to us.

We fed and curried the horses, RedBird and Miss Blossom. We also cared for the chickens and tended to the flower and vegetable gardens.

Our apple trees were harvested by next-door neighbor Joshua Teems and his sons, Isaac and Jacob.

Mr. Purdy, the butcher, dressed out the occasional sheep or pig I raised as a member in good standing of the 4-H Club. Butchering days were painful. I raised those animals practically from the day of their birth, and by the time they had grown to eating size, they’d become the dearest of friends.

Whenever Daddyboys loaded the truck for a mournful trip into town, I hid out down by the pond, so as not to hear the awful squealing and bleating that echoed in my head long after the truck was out of sight.

These woebegone episodes of mine prompted my grandmother to cluck her tongue and pronounce that I would never be a farmer’s wife. “Too much poetic soul,” she would observe, not unkindly. Prophetically, as an adult, I don’t eat anything with four legs.

Thankfully, there would be no butchering today. Instead, Francesca and I would take a delicious detour from our chores.

“Let’s ride RedBird and Blossom to the swimming hole,” I suggested, already skipping down the back stairs. I knew exactly what Francesca would say, which she did.

“But of course.”

In the kitchen, Francesca and my mother exchanged polite greetings.

“Good morning, Rachael.”

“Good morning.”

Their relationship was not distant, exactly. It did, however, exist on rather strictly defined terms. They were generous to and thoughtful of one another, but I never saw them in one another’s pockets.

My mother was practical and outspoken; my grandmother was grand and outspoken. My mother was rooted to the earth; her mother’s feet always rested on a mountain top, the better to look down upon your little world and keenly observe every single thing that happened in it. My mother was business-like to the point of briskness and rather cheerful. Francesca was … well … more like an empress in a folktale. She was cooler, deeper. By some accident of birth, they had been thrown together like clashing colors in a crazy quilt.

“Wherever did that come from?” Francesca said, pointing to a tiny replica of the Eiffel Tower that sat rather haughtily on top of the ice box.

“Why, I’m sure I don’t know,” my mother answered. “I thought maybe Sarah put it there.”

“I can’t reach that high,” I said. “Besides, what would I want with that old thing?” Of course, whatever I may have said, my interest was piqued. I have always loved a mystery.

Mommy smiled and took my face in her flour-scented hand. “It’s amazing that you can reach that high when spice cookies are cooling there. My daughter, the ‘stomach,’” she said with a shake of her dark blond hair.

Rachael could be warm and kind, but she could be stern, too. I learned to address her according to her mood, which is why sometimes I called her “Mommy” and other times it was “Mother.”

Today she was on a very even keel, quite unlike Daddyboys’ unusual antics and newfound love of popular music. Maybe we were about to find out what in the bejesus was going on.

At that moment, my father breezed into the room, wearing a Sunday shirt and smelling faintly of vanilla. He grabbed my mother and began waltzing her around the kitchen.

“Clay,” she sputtered, “what on earth? What has gotten into you this morning? Surely you don’t plan to go to work dressed like that?” Francesca and I traded knowing looks. Something was definitely up.

With a little huff, Mom pulled away from Daddyboys, who laughed, kissed her loudly on the cheek and disappeared out the back door. Wham, went the screen.

“I wish he wouldn’t slam it like that,” Mother sighed, staring after him with a frown.

My grandmother returned her attention to business.

“What can we do for you today, Rachael?”

There was a long list. Mary Porter was coming at ten to pick up the pies, and Mrs. Sweeny would be there in the afternoon for the laundry.

“I think the peas are ready, too,” said Mother. “You could clean and shell them. And chuck the corn, will you?” My mother looked at me sharply. “Just don’t eat all the peas.”

“Don’t worry; we won’t,” said Francesca as we went out the back door and down the stoop.

“And don’t let the screen door …” It was too late; slam!

The barn stood across a side yard, where grass struggled to find the sun under a broad elm. Francesca whistled softly, and RedBird nickered from her stall. Anyone who saw those two together, the woman and her horse, would have sworn they’d been sisters in another life. When Francesca communicated with her mare in that quiet way she had, RedBird’s ears pricked up. They gazed into one another’s eyes like long-lost friends. No matter how far out in pasture RedBird was, when Francesca whistled, that horse would come running. Francesca rarely used a saddle and never a bit, preferring a simple hackamore.

“After all,” she’d remind me, “you don’t steer with your hands. Just a little knee pressure suffices.”

Let’s just say I hadn’t quite mastered that technique. Francesca said it was because the riding was still primarily in my head.

“It needs to come right from your blood, from all your muscles, from your heart.”

Francesca was a great one for doing things from your heart. Things you’d never thought of as having anything to do with your heart. Like schoolwork and sewing and even weeding.

After we replenished food and water for RedBird and Miss Blossom, Francesca helped me saddle up. With a click of her tongue, she set RedBird into motion, and Blossom followed alongside and slightly behind.

Miss Blossom was under fourteen hands, fat and dappled. She’d had a hard life. You could tell by the scars on her knees. By the time Daddyboys bought her from a scrawny, mean-looking little man named Hoffstedder at the county fair three years back, she’d sunk pretty low. She was skinny and saggy in the middle, and there was dullness in her eyes that made my stomach knot. Under Francesca’s care, Miss Blossom had regained her weight and had even developed a sunny disposition.

Daddyboys was against purchasing Miss Blossom at first.

“I don’t know, Frances,” I remember him saying. “She’s the right size for Sarah, but I don’t trust that look in her eyes.”

But I, in the odd way of some small children, had fallen in love with the ill-used pony, convinced that if I didn’t have her for myself, no one would ever love her again.

“Please, Daddyboys? Oh, pleeease …”

Francesca had been quietly studying Miss Blossom for some minutes while my father contemplated the matter. She stepped up to the mare’s muzzle and blew softly into her nose. Miss Blossom snorted back, softly.

“Well, now, Clay, I appreciate your feelings. You know I do. But I have a sense about Miss Blossom.”

Francesca’s instincts about horses were similar to my father’s own senses about machines. He bought Blossom without uttering another word.

Sitting in the saddle now, looking down at Blossom, I couldn’t help but think how really great a horse she’d turned out to be. As we trotted down the gravel drive to the road, Francesca interrupted my thoughts. “Which way should we go?”

“Let’s take the long way. I’m not too keen on seeing Isaac or Jacob.”

“Does someone have a little crush on someone?” Her eyes were twinkling devilishly. I was no fool, even at that tender age. I deftly rerouted the conversation. “Daddyboys has a secret! I’d give dollars to doughnuts to know what it is.”

Francesca pursed her lips slightly and turned things over in her mind for a moment or two. Then, “Yes, he’s got something up his sleeve. You know, Sarah, there’s more to your father than meets the eye. I wonder … It’s going to be an interesting couple of days.”

She began to hum La Vie en Rose softly.

Chapter 3 Unexpected Delights

My family lived on a piece of land that had once been part of a much larger tract. Francesca’s forebears had begun arriving in Lost Nation in the 1850’s, having survived a treacherous migration from Essen, Germany. Their stories, which were handed down by the generations with assorted embellishments, were hair-raising and full of ingenious creativity.

Farmers they had been in the Old Country and farmers they would be in the New. With their detail-oriented industriousness, the German settlers, many of them Pittschticks, were soon enjoying a vigorous prosperity and did so for about seventy years. But then, the Great Depression hit hard.

The family dug in for a grim battle with the American economy but came up losers. Little by little, bits of land were sold off from the thousands of acres that had been Home Farm, until only the last twelve were left. With farming no longer a career option, the Pittschticks became mechanics and teachers and Presbyterian missionaries traveling into the darkest regions of Africa—and California—to spread the Gospel and save so-called lost souls.

By 1947, Francesca, Rachael and I were the only descendants left out of a once-thriving colony of cousins. Home Farm, as it was still called, was not jointly held by my parents; it belonged to my great-aunt and grandmother equally and would one day belong to my mother and me. As my Grandpap had been a Schneider and my dad a Morgan, they were not eligible to inherit.

This morning, Francesca and I rode along the western boundary of Home Farm on Thunder Ridge Road, the main drag into and out of Lost Nation. There was supposed to be an actual Thunder Ridge up in the hills somewhere, and I’d always wondered where it was and where the name came from.

My grandmother, who loved thunderstorms, with their great booming claps and corkscrew lightning bolts, insisted that those hills were the site of ghostly native rites. According to her busy imagination, long-dead Indians, their spirits keening and hollering, danced around spectral campfires. And it was true that whenever the thunderheads rolled in and draped our uplands in the purples and earth-tones of Apache blankets, I swore I could hear those phantoms in their celebrations.

RedBird was a whiz at anticipating Francesca’s moods. With scarcely any prodding, she took the path that led down to the fishing pond. It was swim time!

We tethered the horses and stripped down to bathing suits. In a flash, I was up to my ankles in the chilly water, but no matter how quickly I moved, Francesca always seemed to get there a tad ahead of me.

I was what my grandmother called an “inch-by-incher,” letting one part of my body at a time become accustomed to the shivery cool. Francesca (who had worn bathing suits under her farm clothes for decades) always dove right in head first, with little regard for the temperature of the day or the water. Never a fan of the Australian Crawl, she dog-paddled a little, and we started to splash one another, with me shrieking every time the icy droplets hit my still-dry back.

Suddenly, I glanced beyond Francesca and spotted what looked like a dead crow floating across the water. There was a rookery on our property, and since this was the time of year when fledglings were learning to fly, we found the noisy black birds—adults and youngsters—in the darnedest places. But this was the first one I’d ever seen in the pond.

Francesca took up the still form in her right hand and held it up to her ear like a sea shell.

“It’s still alive,” she said.

“Can we save it?” I asked.

Without answering, she waded over to the bank, took up her soft cotton shirt and gently dried the still body. Francesca peeked under its wing and discovered down, which meant this was not a crow at all but a baby raven.

“What should we do?” I asked.

Francesca determined we’d return to the house, where we could better tend the tiny, sopping survivor.

“Sarah, you carry it now.”

This was an unwelcome surprise. I was not allowed, by parental edict, to touch any of the chick hatchlings, for fear I’d be too rough and hurt them somehow. At age five and in a fit of love, I had smothered one to death with my tender but heavy-handed caresses. What if something bad happened now?

When I felt prickling behind my eyes, I screwed my brows together and forced my eyes into slits to hold back the tears.

Reading my mind, Francesca put her free hand on my shoulder.

“It’s time you left that nonsense behind. You, of all people, who wouldn’t hurt a fly or eat a farm pet even if you were starving.”

She looked into my eyes and smiled, but I didn’t smile back. I took a deep breath and set my mind to the task.

Using a stump as a boost, I scrambled up onto Miss Blossom’s saddle, finding the stirrups with my feet. Francesca handed me the baby raven, gathered up our clothes and hopped up on RedBird.

We started off, with Francesca leading Miss Blossom by her reins. I paid no mind to anything but that tiny living bundle cradled in my hands.

We rode onto Thunder Ridge Road and saw a cloud of dust closing fast. When I heard the rattle-a-tap of the truck, I realized that it must be Hunny Clack out early with the mail.

In the days before the war, Greely Clack had been the Postmaster of Lost Nation. When the draft scooped him up along with my father, they were sent to Camp Dodge, Iowa’s only military training installation.

During the First World War, Camp Dodge had been one of sixteen national training centers and was deactivated shortly after the Armistice. But when World War II broke out, the federal government dusted the place off, swept out the mothballs, patched up the roofs and commissioned it as an induction center.

Daddyboys’ tour of duty took place from 1942 to 1945, in the lower 48, mostly as the head mechanic of motor pools. He was happy enough doing what he loved to do, what he figured he’d been born to do. But his best friend had been restless.

As soon as Greely got through basic training, he requested a transfer, hoping to get to any place with some “real action.” He was eventually posted to England, where he helped censor GI mail, mostly striking out any references to the soldiers’ whereabouts. Greely Clack’s ultimate task was to make sure General Eisenhower’s D-day plans stayed a secret, and Greely Clack did his job. In the event any American mailbags fell into enemy hands, they wouldn’t learn one single thing from correspondence passing under Clack’s watchful eyes and black laundry marker.

With Greely overseas and Lost Nation needing a post person, Hunny applied for the job and got it. A small, round woman with a fresh-scrubbed complexion, her hair was honey-colored and usually hung in a fat braid to her knees. It was her crowning glory and the source of her nickname.

It took Hunny a while to comprehend the postal way of doing things, but eventually she mastered the job and enjoyed her independence and new-found standing in the community.

When Greely finally mustered out of the Army, it was impossible for Hunny to consider stepping back into the shadows. Instead, she declared she would share the job with her husband, who knew better than to object. And since the Census Bureau predicted Lost Nation’s population would be increasing, the county Postmaster kept them both on.

Rattle-a-tap, RATTLE-A-TAP! The truck got louder as it got closer.

Although our exchange with Hunny Clack was less than two minutes, it seemed an eternity to me, and all I could do was stare at the little bird.

The window of her truck was already rolled down when she screeched to a stop alongside us. Peeking through instead of over the steering wheel, she waved and grinned.

“Hi ya,” she called over the noise of the still-knocking engine. “you headin’ back to Home Farm?”

Francesca nodded.

“Great! Can you take this with you? It’s for Clay.”

Francesca nodded again as Hunny handed a larger-than-normal envelope.

“It’s special delivery. It must be important. Hope it’s happy news.”

As Hunny drove off with another cheerful wave, Francesca turned to me. “You know, Sarah, the war was a terrible thing for most people. But it was quite a boon for Hunny Clack. Hmmm … I wonder if this … has anything to do with your father’s little game.”

“Of course it does,” I answered fake-nonchalantly, pretending to think about something other than the bird in my hand.

Francesca then said idly, “Would you say you were about as tall as Hunny Clack?”

“Gee, Francesca, she’s practically a midget! I’m at least as big, probably bigger.” I carefully shifted the baby raven from my right hand into my left. “Who’d write Daddyboys and have it be so important, and all?”

Francesca examined the envelope and noted the return address: New York City.

“We have relatives in New York,” she observed.

“But if someone died, or something, wouldn’t they telephone or send a wire?”

“Absolutely. How’s that bird?”

“It’s moving its claw, the right claw! What should I do?”

“Don’t do a thing, Sarah. The life’s coming back into it little by little. The legs will move next.”

And they did.

We rode along like this all the way back to Home Farm. Hovering between panic and despair, I’d pester her by observing every tiny change in the raven’s behavior. Francesca continued to assure me that everything was going along perfectly and not to worry. She had the patience of a tomcat stalking a lizard.

When we finally reached Home Farm, the raven was beginning to squirm. I was terrified I’d have to squeeze it to keep it from falling to the ground.

Francesca herded the horses into the paddock and ran into the house for a dish towel. She arranged it across the wicker table, and I carefully set the raven down on top of it.

It was beautiful, with feathers so glossy black they looked blue. It kept looking up at me, cocking its head quizzically this way and that, as if trying to make out the secrets of Home Farm … of which there had certainly been a sufficiency that morning.

Francesca brought out a saucer of water along with an eyedropper and quenched its thirst in this way. “Now, it’s up to the raven. We’ll keep an eye on it, and I’ll ask Rachael to watch it from the kitchen.”

My mother wasn’t the kind of person to take this type of duty very seriously. She seemed rather indifferent to animals and their feelings unless she was folding parts of them into pie dough. She wasn’t cruel or unthinking; she was just so brisk and busy, up to her elbows in flour and mixing bowls and recipe cards.

I watched through the back door screen as Francesca spoke to Rachael with low tones and animated gestures, pointing in the direction of the raven. I snuck closer, so I could hear.

“It’s important, Rachael. I want you to mind that bird and no nonsense.”

Rachael nodded absently, and Francesca gripped her shoulders.

“Are you listening? I know this is your busiest day of the week. But if anything happens to that bird out there, I will make your life a misery. And you know I can do it.”

This time, I saw Mother’s eyes focus, and she shrugged off Francesca’s hands. There was an odd expression on her face that met somewhere between annoyed and unnerved.

When my grandmother rejoined me on the porch, the raven was attempting to stand.

“I want to call him Humphrey,” I said.

“You do?” She looked puzzled for a split second before saying, “Well, of course you do. Humphrey will be fine here for a while. Let’s go find your daddy.”

My father worked out of his garage, which was in reality just a drafty converted barn that sat at the southwest end of our property.

Two driveways led to it from Thunder Ridge Road, one bypassing the main house completely so that we were seldom bothered by Daddyboys’ customers.

A walk to the garage always took longer than expected, because Francesca stopped every few feet to examine a strand of sweet peas or a young bed of oregano, muttering mental notes to herself all the while.

“This one needs feeding. I’ll have to pinch this back. Crikey! How did this get so dry?”

To her, gardening was like minding a brood of naughty children. Where Mommy cooed to and seduced her stove, Francesca scolded and praised her plants by turn, attempting to keep them in some kind of mystic balance.

Daddyboys was giving the once-over to Mr. Blackfeather’s 1913 Ford. Everyone in Lost Nation was amazed that the ancient contraption still ran, but my father was a genius with all things motorized. When he swore he could fix an airplane engine with a screw driver and a coat hanger, most people believed him.

Mr. Blackfeather was Lost Nation’s barber. His face was as fierce as any Indian chieftain’s, making him quite a sight when wielding his straight razor. In fact, I often wondered why our neighbors trusted him to use that glistening blade so close to their necks. But as he was the only barber in Lost Nation and environs, they didn’t have much choice.

As we approached the garage, I could hear the men talking.

“I know you can fix it, so you fix it,” Mr. Blackfeather said with deliberate intention.

“It’s not that simple, Tom. I just don’t know where I can get the brake fittings I need.”

“You’ll get ’em. You will, because you always have. And if you can’t get ’em, you’ll get ’em anyway.”

Tom Blackfeather loved that old collection of nuts and bolts. For years, my father had tried to talk him into getting a new car, or even just a newer car, one he could depend on. But Tom refused to contemplate such faithlessness. So the old black Ford kept breaking down, and my father kept patching it up.

Daddyboys sighed. “I can’t get to it today, Tom. But if you can leave it with me, I’ll start first thing in the morning.”

“Okey-dokey. I brought Totem. I’ll just ride ‘im on home.”

Totem was Mr. Blackfeather’s paint pony. On any given day, you’d see it trailing along after the old Ford, connected by a long rope. Totem was a lot more dependable than the car and didn’t seem to mind the cloud of gas fumes that spewed out from the exhaust.

As Tom swept out with a solemn nod to us, Daddyboys saw the package in Francesca’s hand. His face changed color, paling noticeably.

“What is it?” he asked.

“It’s from New York,” Francesca answered

“Open it! Open it!” I couldn’t contain myself a second longer.

Daddyboys took the manila envelope and turned it over gingerly in his hands, like it was filled with explosives. Finally, he held his breath and slit the flap open. Then, he smiled, a dazzling light-up-your-eyes smile that made you want to please him and hug him. Without a word, he folded the letter back up and began to hum an old favorite, “How You Gonna Keep ‘Em Down on the Farm.”

“Is someone gonna tell me what’s going on here?” I asked rather bluntly.

But Daddyboys was lost in his private thoughts, meaning there would be no revelations from him until he decided it was proper.

I kicked up some dust on the dirt floor of the garage.

“Sarah!” Francesca shouted as she pulled me outside into the daylight.

“What?”

“Happiness is a treasure, Sarah, especially someone else’s. It is therefore civilized behavior to think carefully before you set about spoiling it.”

She took me firmly by the hand and walked me back to the porch, where Humphrey was showing signs of a complete recovery. He was about to become a moral lesson, though I’m sure he was ignorant of the fact.

“Let’s take Humphrey as a for-instance,” Francesca began. “What if your mother had been too busy or too unconcerned to watch him, and he’d fallen over the side of the table and been eaten by the Teems’ cat?”

“Francesca!” I protested.

“It would have hurt you. Your mother realized this fact and took a little bit of care about it. Just a little bit of care is all that’s required most of the time.”

As you can see, Francesca used peculiar discipline. She never griped at me for not making my bed or for tracking mud across the kitchen floor or letting the screen door slam. Her concerns had more to do with spiritual tidiness. She gave me a walloping great hug and finished up with, “I love you, Sweetchild. You’re going to grow up to be the cat’s pajamas!”

Humphrey began some serious cawing. He seemed to be expecting some kind of answer. And sure enough, within a couple of minutes, he got one. It must have been his mother squawking back from the elm, obviously urging him to fly to her. Humphrey was still a little the worse for wear and moved like Joshua Teems after a jug of hard cider. But the mother bird persisted. Pretty soon, she was joined by a fistful of other adult birds, and they all began calling. Whenever Francesca started to approach Humphrey, they screamed at her to keep away. Humphrey became more and more agitated and finally flew up to join them. An immediate quiet settled down on Home Farm, which led me to think those ravens knew exactly what they were doing.

In fact, about three days later, the entire rookery gathered together and began to caw, just at sundown. Neither Francesca nor I had ever heard them do that before. We decided they were singing a psalm of thanks for the miracle of the return of their beloved brother Humphrey from the land of the dead. It gave me the goose bumps.

That night at dinner, Daddyboys came to the table dressed in a suit and tie and polished shoes! He brushed past Mommy several times and hummed into her ear. When he took her in his arms and began dancing her around the room, she decided she’d had enough.

“I’m tired of this mysterious behavior!” she said, using her hands for emphasis. “Staying up late at night; writing at all hours; singing French songs; wearing Sunday clothes. And now all this dancing. Clay! What is going on around here?”

My mother could be loud and physical on occasion. Frankly, it ran in the family. But my dad didn’t pay any attention. He just smiled and shrugged himself loose from her grip. He went to the Victrola phonograph in the parlor and turned up the sound so we could hear a new Edith Piaf recording.

She was performing a tune she’d written in 1945 that went on to become known as her signature song. But for the life of me, I couldn’t understand why my father was attempting to sing it now as he pirouetted across the room.

“C’est toi pour moi, moi pour toi, dans la vie

Tu me l’as dit …”

Then, he gathered up the tiny Eiffel Tower on top of the ice box and proceeded to place it ceremoniously in the middle of the trestle table. I figured he’d gone right around the bend, like his Aunt Beedie, who sometimes thought she was Catherine the Great.

Though my mother was clearly irritated, Daddyboys was not deterred; he kept right on dancing and singing:

“It is you for me, me for you, in the life

you said it to me…la vie en rose.”

Then, my father began to laugh. It was a rumbling laughter that came right from his toes. He gathered Rachael up as easily as a doll and set her gently on a ladder-back chair. As he gathered himself together, we all waited excitedly for his news.

I held my breath. You could have heard a biscuit drop. Francesca sat calmly, but the flush on her cheeks betrayed her curiosity.

“Rachael, I’ve won a contest,” Daddyboys beamed with delight.

“A contest, Clay?”

“Yes, a contest, in World Travel magazine. You know, sweetheart, the one you always pore over at Purdy’s?”

My mother sighed in relief and clapped her hands. “And you’ve won a subscription for me; is that it? How lovely!”

“No … not exactly. I won a trip to Paris.”

The words hung suspended in the air. My mother seemed unable to speak for an eternity. “Paris. Paris, France?” she finally whispered.

“Umhmm. Paris, France. That’s right; that’s right! We’ll make a stop in New York and then board the Queen Elizabeth, which will sail across the Atlantic all the way to Cherbourg, a lovely town in Normandy. Then it’s on to Paree where we weel stay at a luxe otel,” my father said with a hand flourish, using a French accent for emphasis. Then he fingered an imaginary moustache, puffed out his chest like a rooster and practically burst his shirt buttons.

“During the war, most of the great steamships were refitted to carry troops. Now, they’re being reconverted, so, to generate interest in overseas travel, cruise ship lines have been running promotions, many in the form of contests. World Travel co-sponsored this publicity campaign, and I won it! I won a trip of a lifetime!”

Mommy sputtered, “This is why you’ve been prancing about? But how? I still don’t …”

“It was an essay contest: Dreams of Paris. Of course, I added a little something to my title … I called it: Dreams of Paris, Dreams of Love.”

“And you didn’t tell me? Exactly how long have you known?”

“They wired a couple weeks ago, I guess. But it wasn’t final until today.” My father was still grinning. Then, Mommy got the giggles. She started laughing uncontrollably and holding her sides, pointing at my father and shaking her head. She tried to speak. “You … essay … Paris, France?” was about all I could decode before Mom had to run upstairs to the bathroom.

Daddyboys looked a little shaken by this response, so Francesca stood up and put her arm around his shoulders.

“No two ways about it, Clay … I’m stunned. Obviously, Rachael is, too. But we’re all proud, so very proud,” she said, and she kissed him on the cheek. “Now, why don’t you go on upstairs? I’ll bet Rachael is settled down by now.” Francesca gestured toward the staircase. “Go on,” she said quietly.

Clay took the stairs three at a time.

Long into the night, I heard playful noises coming from the master bedroom. At one point, I even heard the unmistakable pop of a champagne cork. Now, you may think I didn’t get a wink of sleep with all those goings-on. And you’d be right. But this celebration was better than sleep. It was like having the most wonderful dream while you were still wide awake.

BUY NOW:

Autographed copies / Amazon / BN /

DON’T FORGET to PURCHASE the Companion Song –